by Eileen Le Guillou

In my previous post covering art highlights over 6 months, I touched on the surprising early works of Monet and Rothko. I expand on their stories here, and introduce several others including Calder and Kandinsky and their lesser known masterpieces. Before (and after) these artists were known for their iconic, singular styles they explored very different aesthetics. As if going back in time with them before they knew what they would become, we glean hints of their personality and inspirations, and explore why they changed and when they became truer to themselves.

Monet

Ingrained in the evolution of many of our favorite artists are stories of political and social unrest, wars, personal life events, and mental illness, but Monet’s story is one of the more lighthearted and relatable. A wealthy upbringing is often a prerequisite for many artists of the past and still today. Countries around the world and the United States in particular continue to cut their investments in the arts and in turn their global influence. Born without wealth or status Monet, again, proves to be an exception.

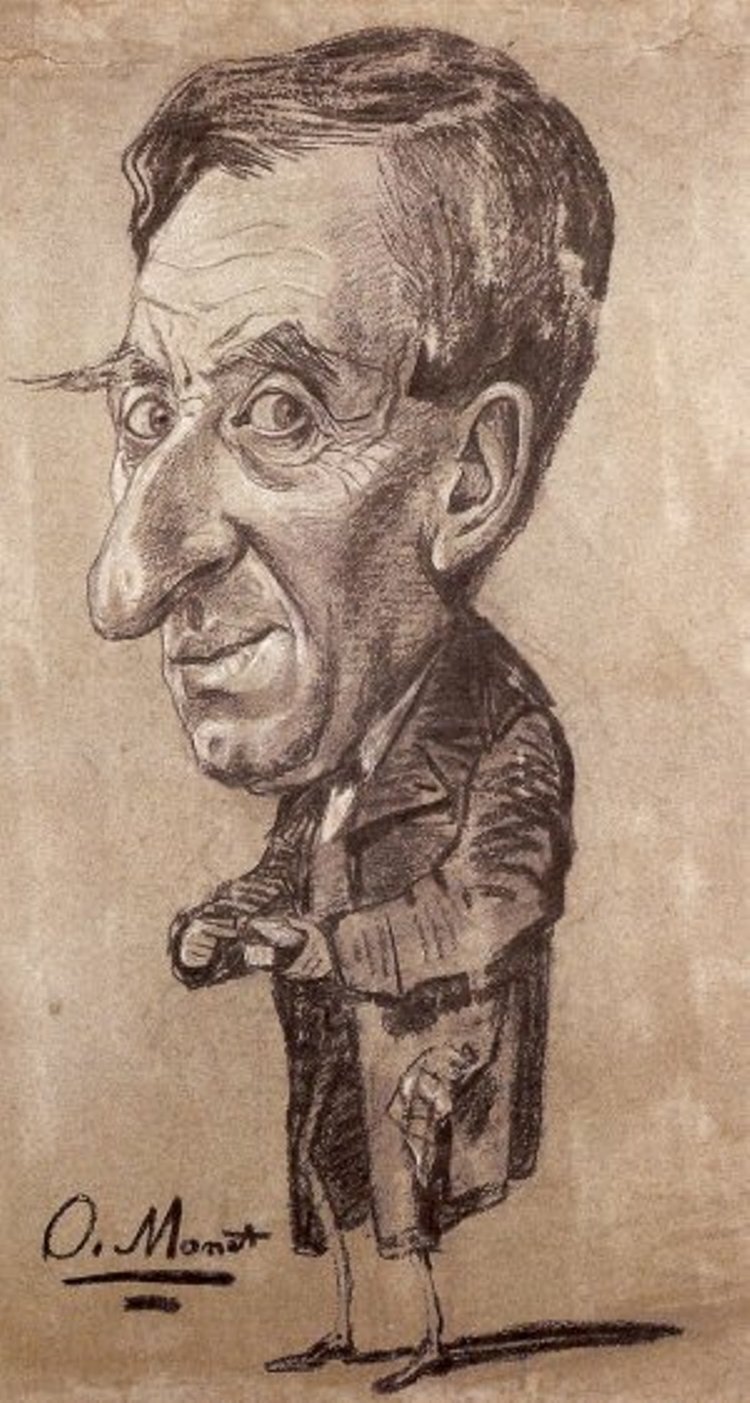

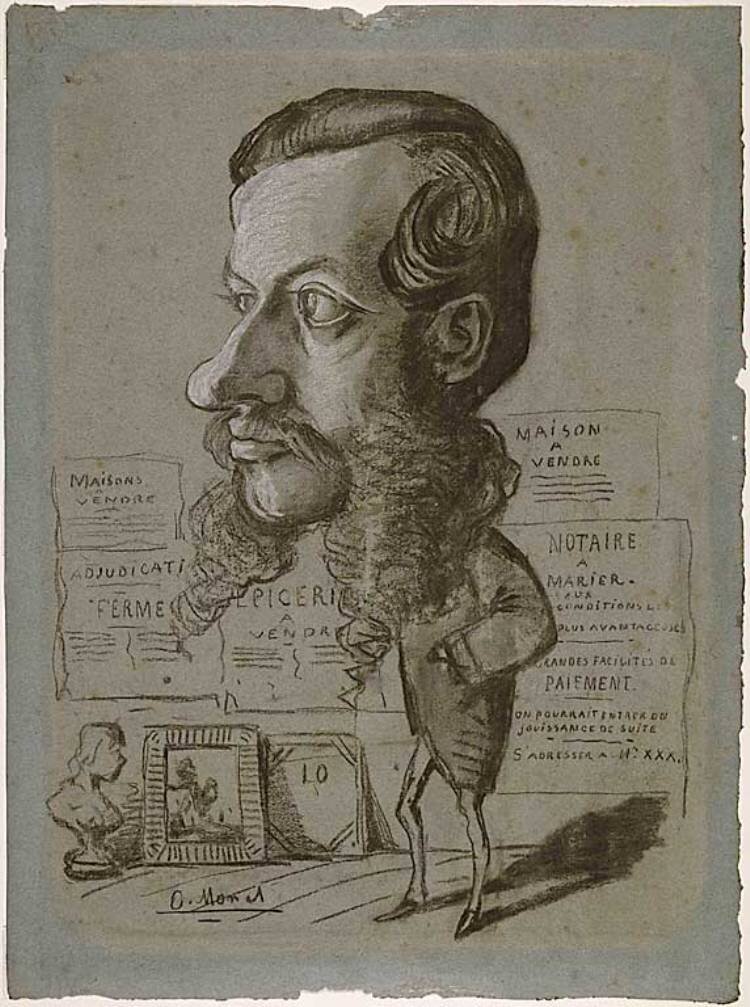

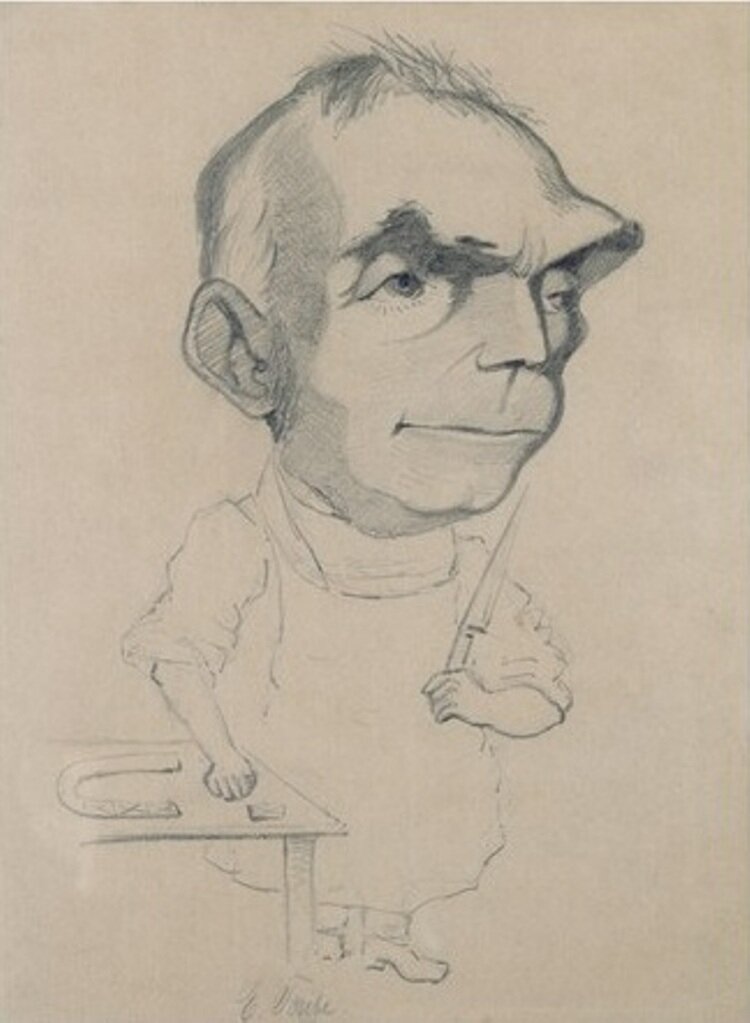

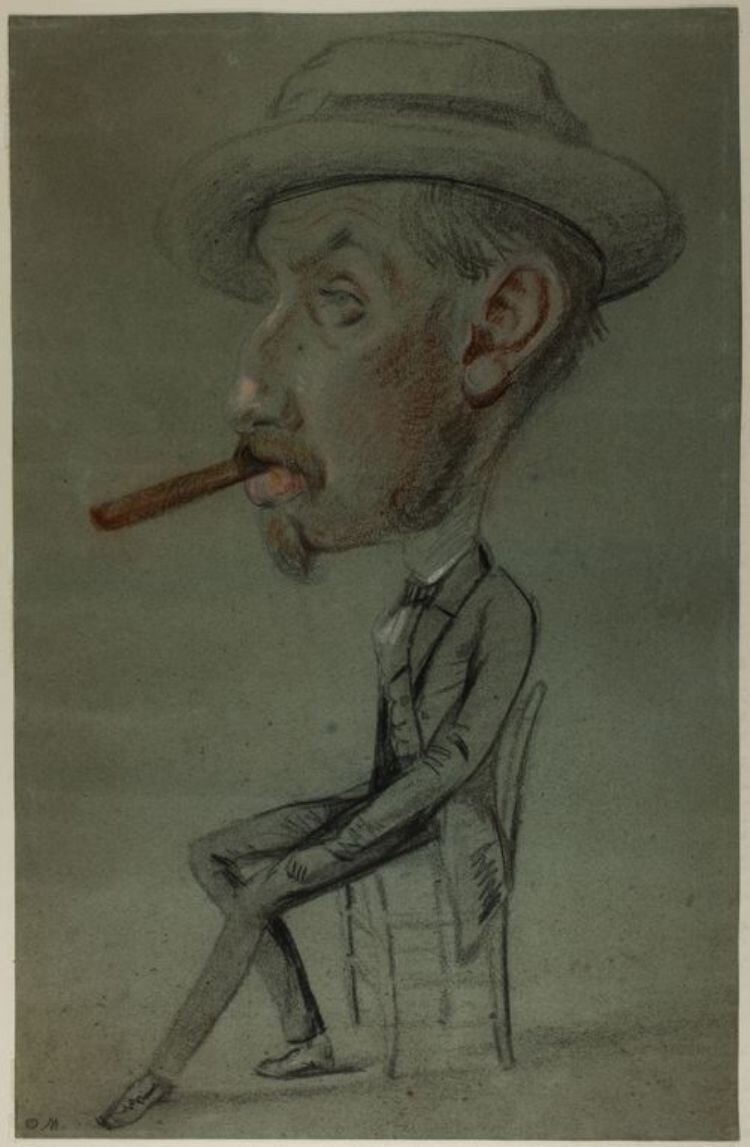

Raised in Le Havre, 16 year old Monet became known about town for drawing humorous caricatures of local town characters. His ability to capture their personalities and expressions were so perceptive that shopkeepers began commissioning his work for their windows to attract customers, but he had no intention of pursuing art as a career. A local painter, Boudin, saw the drawings and in them great potential. He encouraged Monet to study painting and find his subjects in subtler forms of nature.

Monet initially resisted the urgings of Boudin but eventually gave in and changed the trajectory of his life. He wrote: “Summer came, my time was more or less my own, I could hardly put him off any longer. So to get it over with I gave in and Boudin, with unfailing kindness, took me in hand. In the end my eyes were opened and I gained a real understanding of nature, and a real love of her as well."

And so Monet developed into the artist we now associate with water lillie’s and familial scenes. Not until the early caricature drawings were gifted by Carter H. Harrison to the art institute of Chicago - 70 years after they were made, in the mid 19th century - was Monet’s past even known to the public. What makes these caricatures so special is that we see the humorous side of Monet and glean some sense of his opinions that are masked in his later, more professional works. He was able to express what he thought and what the locals in his town could understand and appreciate, rather than what was palatable for universal appreciation and admiration.

Rothko

Mark Rothko emigrated to the United States in 1913 from Latvia during a wave of Jewish emigration to the United States, and later became a pioneer of the abstract expressionist movement that evolved after WW2.

While at the Art Student’s League Rothko was encouraged by Max Weber to work in Paul Cezanne’s figurative style. Weber also showed him that art could be used as a tool to express emotions. Below on the left is a painting by Cézanne, Bouilloire et fruits, 1888–90, and on the right is Three Nudes, painted by Rothko in 1933-34. We can see the influence of Cezanne’s palette and figurative style.

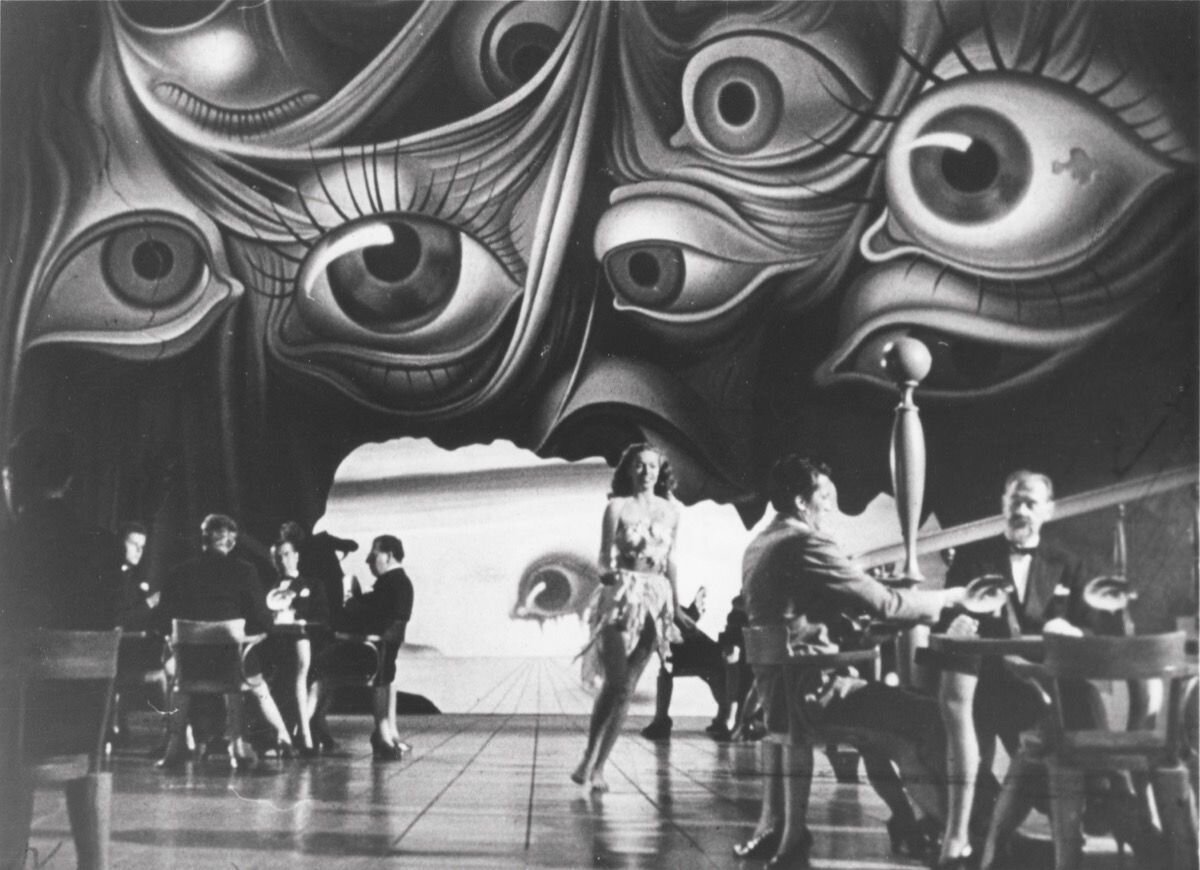

Underground Fantasy, 1940

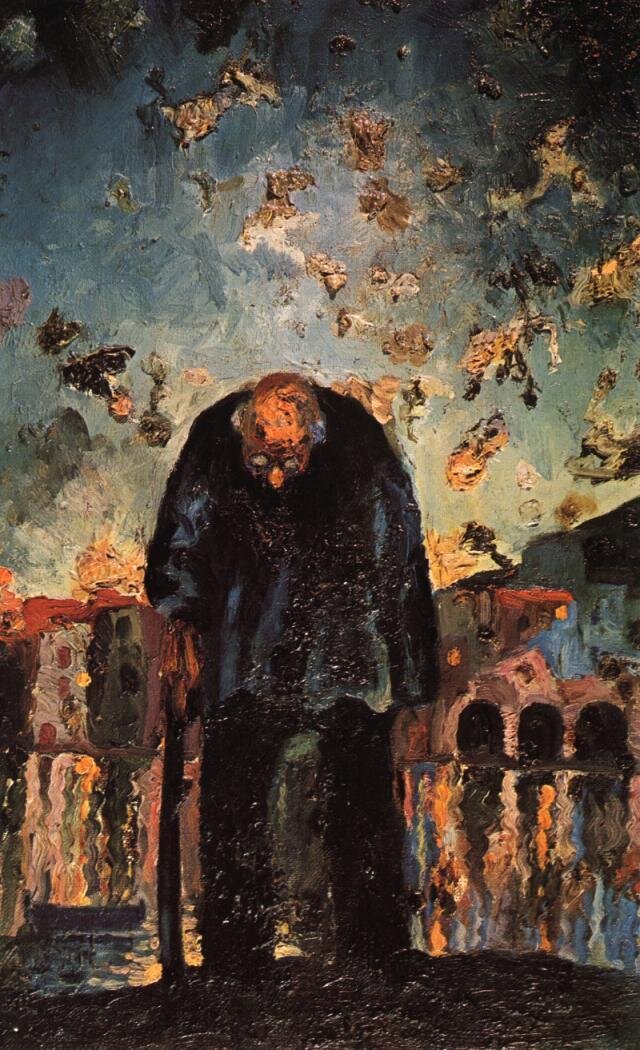

During the 30s and 40s, we see Rothko experiment with proportion and perspective as his human figures become more abstract and flat. As with fictionalized stories, exaggerated forms and features can convey more accurate feeling and emotion than literal representations or realism - something Monet understood with his caricatures.

As Rothko progresses, his figures become even more abstracted into color blobs. In these we see hints of what comes to define him in his later works.

He attempted to remove associations that the viewer may have - obstacles as he called them - by removing all references to the natural world including titles and explanations.

“With us the disguise must be complete. The familiar identity of things has to be pulverized in order to destroy the finite associations with which our society increasingly enshrouds every aspect of our environment.” - Mark Rothko

He later reduced the number of color blocks and maintained a somewhat consistently structured format. He used only variations in tone, saturation and hue to create dimension on the canvas. By doing so, he could create controlled moods and atmospheres.

He made his paintings large so that they would be intense and consume much of the viewers field of vision. To me, viewing a Rothko painting has always felt like an immersive experience, now common in galleries around the world. Many miss the beauty of a Rothko: they are meant to hang low at the viewers eye level within confined spaces with dim lighting. Absorbed in this way, have the intended effect: they create a primal stir within the viewer, with no obstacles between them and Rothko’s meditations.

Mondrian

Initially influenced by Vincent Van Gogh, Piet Mondrian’s early works show bright exaggerated colors and heavy brush strokes.

Devotion, 1908

After being exposed to cubism, Mondrian moved to Paris from his native Amsterdam and embraced the style and simplified color palette - even simplifying his dimensions down to two.

Composition in Oval with Colour Planes, 1914

Mondrian’s motivations were similar to Rothko’s - by removing the visual associations to objects in our material world, he felt he could express a deeper truth: “to articulate a mystic conception of cosmic harmony that lay behind the surfaces of reality”. Mondrian joined the Theosophical society in 1909 and he, like Kandinsky and Rothko, believed in the Theosophical teaching that the perceived world is an illusion and to be limited by these perceptions is to be ignorant. Further, they believed that wisdom results from uniting our physical beings with our higher selves.

Following the end of World War I in 1918, Mondrian embraced pure abstraction. By 1920, he had developed the grid pattern filled with only three primary colors (red, blue and yellow) that he would iterate on for the rest of his life.

Calder

When it comes to Alexander Calder, his famous sculptures and lesser-known paintings evolved simultaneously.

After studying and working as an engineer, Calder was inspired to begin painting the world around him and discovered his natural talent for realism . He enrolled in the Art Students League and worked as a newspaper illustrator. Desiring movement, Calder often worked with wire and metal to create three dimensional art.

In 1926 Calder moved to Paris. There, he produced his famous Cirque Calder and in the process he visited Mondrian’s studio where he discovered abstraction. In one of his first attempts at abstract paintings we see the direct influence from Mondrian.

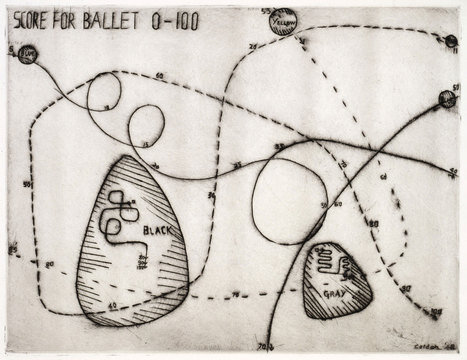

Inspired by his visit with Mondrian, Calder transitioned his sculpture into moving, suspended “kinetic sculptures” or “mobiles”, a term coined in 1931 by Marcel Duchamp. These would become his most renowned and original works.

Untitled, 1934

Prolific and exploratory, Calder made jewelry, figurines, rugs, political posters, theater sets, and monumental ironworks, all while developing his mobiles and experimenting with different painting styles. In one of the paintings below, we see hints of Miro sparked by their deep friendship and similar world views. While diverse in his range, all of Calder’s works across mediums from childhood until death poses his unmistakable fluidity.

“

Well, the archaeologist will tell you there's a little bit of Miró in Calder and a little bit of Calder in Miró.

— Alexander Calder“

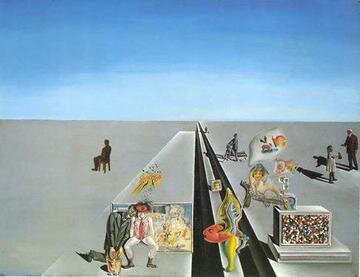

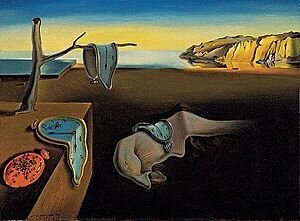

Dali

Known for his create his precise, surrealist artwork, Salvador Dali’s created his first painting - impressionist landscape - as a six year old child prodigy. Below are some unbelievable examples of his work from the ages of six to fifteen, a year before his mother’s death.

Introduced to Cubism and Futurism by his family at a young age, Dali was influenced by Picasso and Miro. It wasn’t until he was 24 that his work took on more Surrealist influence.

While he denounced Surrealism - the artistic form that catapulted him into notary - in 1941, Dali, like Calder, was a versatile artist and ventured into theater, film, fashion jewelry and sculpture.